Kitty Bauer was jumping on a small, indoor trampoline, her wavy hazel hair and light springtime clothes flouncing lightly. While she jumped she seemed to be deep in thought, rather in contrast with the enthusiastic movements of her slight form. Her mother, Dolores, came into the game room with a can-opener in her hand and a somewhat lost expression on her face.

“Kitty, keep your skirt down.”

Kitty pinned the flying pleats to herself with her small tawny hands.

“But why? No one else is here.”

“You should practice being polite still.”

“Oh.”

Dolores pushed her glasses up her nose in a schoolgirlish way (like her daughter, she was small of stature), and, seeming to suddenly remember where it was she was actually going, hurried out of the room again.

Kitty stared out the window at the waving, sunlit grass, and wished her friend Otto Kunger wasn’t doing an extra project for school. It was such a day for “hunting”.

There was a light in the air, like the flash of sunlight off a person’s watch. It glimmered, but unlike reflected light it was moving without going out. Kitty stopped jumping and called for her mother. The light was down in the grass now, scooting fitfully like a blown leaf. It was too bright to make out the colour, but it might have been green, or violet. Dolores skipped back into the room, unconcerned, but sensing the urgency in her daughter’s voice. Kitty stood rapt, her hands still pressing down her now motionless skirt.

“Mum, you remember how you saw the fairy when you were little?”

“Yes.”

“Did it look like that?” and Kitty pointed to the light, which was now rising and falling like a tired bumblebee attempting to fly.

“What… Yes, I remember that. Kitty, run outside and see.”

“Are you coming?” Kitty was already out of the room.

“I’ll just take my sandals…” But these, as usual, weren’t where they were meant to be. “Nevermind, I’m coming.”

On the way out Kitty snatched her butterfly net, which was always kept ready to hand. Her mother caught up with her at the back door, which was nearest.

“No, Kitty, leave that, we must be polite.”

“Alright.” And she let the net fall as they ran around the house. They were glad to see the light had not gone far yet. Dolores held Kitty back from running nearer, and they approached more gently. They were almost coming close enough to see the shape of the thing that bore the light, when it whisked into the air as lightly as if on a breeze, though at that moment the air was still as a pond. It floated away over the dense cedar hedge like a vexatious butterfly, and the girls were left in dismay. In their bare feet they ran to the hedge; Kitty made for a slender tree near at hand and began to climb it like a cat. Dolores shaded her eyes as she watched.

“If only that tree could carry me…” But it was already swaying precariously with Kitty’s meagre weight. Dolores got down on her face and began to scramble through the narrow gap under the hedge. Kitty tightly hugged the branch-thin height of the tree she had reached.

“I see it! It came down in the pasture!”

“Don’t shout too loud.” Her mother’s voice was muffled under the hedge. Kitty deliberately swung her body this way and that, then made a spring when the tree was bent nearest the level top of the hedge.

“Ow.” The prickles had greeted her face and arms inhospitably. Yet she subjected her skin to more extensive scratches trying to tumble or slide down the both yielding and resisting far side of the hedge. Once she had picked herself up from the ground, she began to run, then remembered not to. She looked back to where her mother, puffing and leafy, was emerging from under the dark branches like a mouse from under a church door.

“Go on ahead,” Dolores whispered, “but be careful not to offend it.”

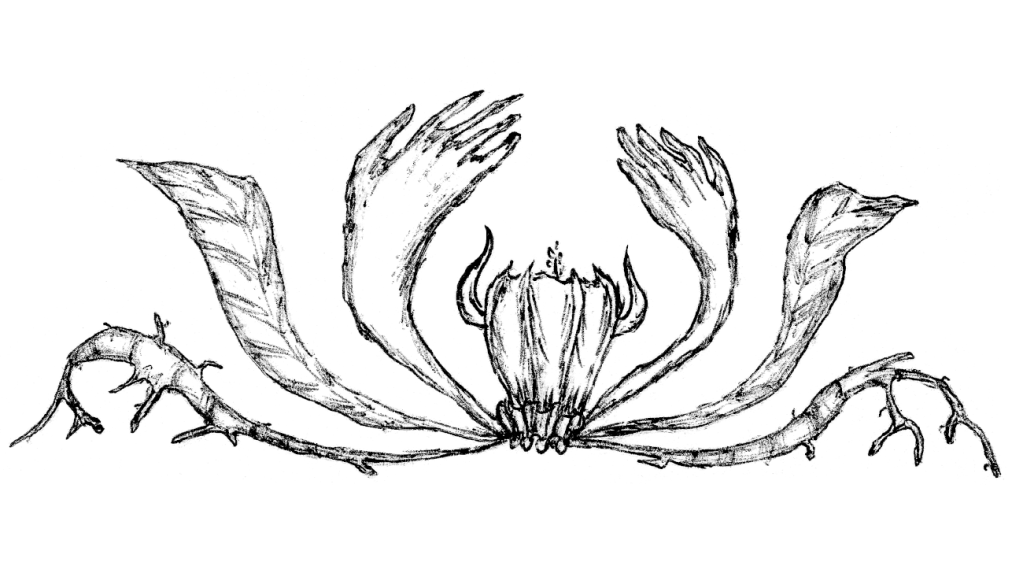

Their goats were huddled at the far end of the field, where they had apparently scampered when the light came down. As she crept closer, Kitty began to see that the shining came from a round, flat thing like a mirror, about the size of a large coin, and there were hair-thin patterns on it. This was carried by something that seemed more like a vehicle than a creature sometimes. Her mother came up, breathing quietly, and not even brushing off all the bits of twigs, dirt, and leaves that were clinging to her. Together they came as near as they dared and bent down, squinting through the petite glare, Dolores holding her glasses so they wouldn’t fall. They saw more clearly now the thing that was carrying the shining disc: it was made of rich, darkish paper, with some floral pattern.

“It’s an origami bird,” Kitty said.

“Or leaf, or boat.” Dolores leaned even closer, then drew back and spoke excitedly under her breath in her daughter’s ear, “It borrowed one of my origami papers; I recognise the pattern.”

The thing seemed to be fidgety, and after shifting this way and that it moved half a yard nearer to the two girls.

“It’s coming to us.” Kitty was breathless at the thought, but Dolores nudged her urgently.

“Move, Kitty. We mustn’t block its path.”

Sure enough, when they had gone a few steps to the side, the light bearer passed hesitantly across before them, brushing the tips of the grass with a faint, tingling sound that made the fine hair stand up on Kitty’s arm.

“Don’t look as if you’re too interested, but it’s going to that hole. Was the hole there before?” Dolores asked.

“Yes, we thought it was a rabbit hole, though there’s only one.”

“It could have been a rabbit hole. Fairies use the old holes of animals sometimes.”

The light bearer paused at the mouth of the dark, earthy hole, then slid and floated down inside it. The light showed the nice brown of the earth deep in the throat of the hole, before it went around a corner and faded away like a candle carried away into a dark house. A curious, foreign kind of smell also faded from the air, unnoticed until it began to leave.

The girls were on their hands and knees, staring after the departing gleam. They looked at each other after it had gone, and did not need to say anything to communicate their happiness. Something strange and wonderful had come to stay with them, at least for the present. As they went down to the gate, Dolores was rubbing her arm.

“I’ve got a nettle sting pretty bad.”

“I’m scratched all over my arms and legs, and cedar scratches itch. But this is such a thing to tell Dad when he gets back! Mummy, are fairies animals?”

“I guess they are, but they’re far cleverer and powerfuller; like angels, only angels are people. I suppose fairies and spirits like that are to animals what angels are to us.”

“If they’re animals, does that mean you can eat them, like chicken or fish?”

Dolores squinted in thought behind her glasses.

“I don’t think it would be right. But I suppose… maybe in some magical ritual. Some spirit-things eat each other I know.”

After they were gone, something else left the field also, rustling low under the grass, while the goats trembled and dared not bleat. Near to the path of this unknown thing, under the bent blades of a tussock, a Devil’s coach-horse beetle and its mate darted over and around each other in fierce, writhing circles, dancing a deadly battle. A passing honeybee veered, and thrust its stinger through a stem, though the bee would die, disembowelled.

Something else had seen the hole where the light bearer came to rest, and ill things were afoot.

Go here to read: The Pasture Watch – Part Two: The Sting

Go here to read all posted so far of: The Kitty and Otto Stories

I’m cross-posting this here and on Hope, Hearts, and Heroes: a blog of six authors in Romance and Speculative fiction.

2 comments on “The Pasture Watch – Part One: The Light Bearer”